Parks for kings, parks for cars, parks for people

In aerial pictures of the Brussels region, Belgium, two large green areas stand out: the Royal Domain of Laeken, situated in northern industrial suburbs of Brussels, and the Bois de la Cambre, in the south, connecting the Sonian Forest to the city.

Alhough both these urban forests have similar ecological properties of many other of comparable size, once we take a closer look it becomes clear that they are very different from the typical urban parks with families picnicking on the lawn, dogs barking at the ducks, and joggers making their weekly exercise. During the COVID-19 quarantine, in fact, the two parks became the stage of two anecdotes that tell us how – in spite of wide agreement on the important ecosystem services that urban forests offers to cities – different and even conflicting visions about their use remain.

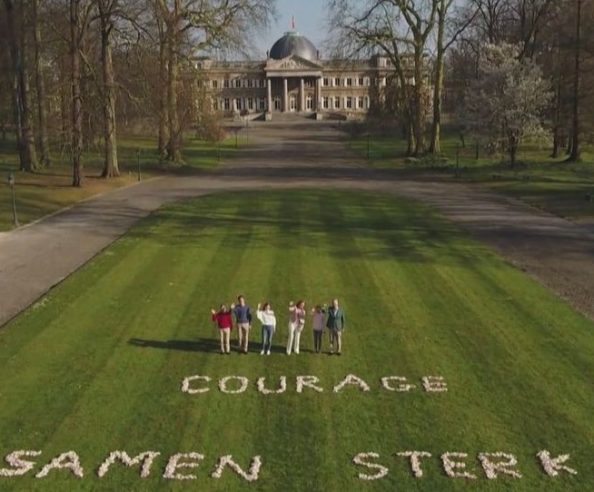

The Royal Domain of Laeken – During the Corona Virus lock-in, the Belgian royal family has published a video taken from the 186 hectares wooded domain, where king, queen, princesses and princes encouraged the population to be strong, reassuring everybody that the country will be able to pass the crisis. Notwithstanding the best intentions of the royal family and of their communication managers, the message was immediately the target of irony on social media and on the public square. In #stayathome times, with less than 25m2 of public green space available per inhabitant, the intended empathic tone of the message was squeaking with the image of flagrant inequality it was providing. More so, with the exceptions of a few weeks of the year during which it is possible to visit the park’s greenhouses, the Royal Domain is not accessible to the public and act as an unsurmountable barrier in the urban fabric. The park is public property and its maintenance costs ca. 1 million Euros per year to the Belgian tax payers. Regularly, citizen movements and politicians of all colors, put the question of the opening of the parks on the agenda, but so far without success.

The Belgian Royal Family at the Royal Domain of Laeken

The Bois de la Cambre – The Bois de la Cambre is accessible to the public. Once among the preferred destinations of the 19th century urban bourgeoisie, the park has long lost part of its charm because of an 8-shaped, urban highway cutting all across it. How the park should be used has long been an issue of contention, and the debate on the place for motorized traffic between the trees is surfacing again in times of COVID-19. Recognizing the need for more and larger green areas to cope with the challenges of the quarantine while respecting adequate distance among people, in fact, the Brussels government had forbidden car access to the park. The park, a sort of Brussels version of NYC Central Park, was open then to all-but-one possible uses and joined the many examples of tactical urbanism that popped up around the world to provide greater livability to quarantined cities.

If the sentiment of national solidarity and the reduced traffic flows had initially sheltered the park from polemics and controversies, the mood started to change together with the slow lifting of the lock-in measures. Many discovered the beauty of car-free urban nature and asked the government to extend the policy sine die, others raised their voice to make sure to go back to pre-crisis set-up. In the Belgian tradition of compromis, the decision was taken to split the park in two, with the northern part open to car traffic during the week, and the southern part open to everything else, with promises of further consideration after the summer.

Parks for kings, parks for cars, parks for people – What do these stories have in common? Both of them tell us that, despite the consensus on the importance of urban forests, in scarce urban land choices need to be made to arbitrate between mismatching priorities. And if you and I might agree on how to use these two parks, the point to be made here is that urban forests are not just a collection of trees. In turn, they are part of a much broader socio-ecological landscape, involving people, institutions, infrastructures, among other things. In these two cases, the aspiration to grant public access to parks for people to enjoy nature or walk through, was confronted with other concerns, namely the privileges a country recognizes to its representatives – allegedly “the last place where the royal family can enjoy total intimacy”- and smooth motorized mobility.

Since neither I nor you have the keys of the gate (well… unless this blog has royal readers), which priority finally primes goes back to the city’s power dynamics, involving democratic decision making, petitions & consultations, vested interests, scientific and technical considerations, path dependencies, explicit or hidden power imbalances… While sometimes the imaginary of wilderness and natural beauty puts them in the shadow, urban forests host a whole range of socio-political dynamics that projects such as CLEARING HOUSE will hopefully help to unveil.

Author: Nicola da Schio, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB)

The VUB is an internationally oriented university in Brussels, the heart of Europe. Through tailor-made high-quality research and education, VUB wants to contribute in an active and committed way to a better society for tomorrow

Nicola da Schio is a researcher at the Cosmopolis Centre for Urban Research at (VUB). You can find more information about Nicola or follow him on social media here: @nicdas13 – www.nicoladaschio.com